Sesame allergy

Sesame allergy is a common food allergy to foods made with sesame (Sesamum indicum) seeds. Prevalence estimates for the allergy is in the range of 0.1-0.2% of the general population,[1][2][3][4] and is higher in the Middle East and other countries where sesame seeds are used in traditional foods.[4]

| Sesame allergy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Raw sesame seeds with sesame plants in background | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Prevention | food avoidance |

| Treatment | Diphenhydramine (anti-histamine) Prednisone Epinephrine (adrenaline) injection |

| Frequency | 0.1-0.2%[1][2] |

Reporting of sesame seed allergy has increased in the 21st century, due either to a true increase from exposure to more sesame foods or an increase in awareness.[1][2][5] Increasing sesame allergy has induced more countries to regulate food labels to identify sesame ingredients in products and the potential for allergy.[6][7][8][9] In the United States, sesame will become the ninth food allergen with mandatory labeling, effective January 1, 2023.[6]

The allergic reaction is an immune hypersensitivity to proteins and lipophilic proteins in sesame seeds and foods made with sesame seeds, including sesame oil. Sesame seed oil is used in cosmetics products, and can cause allergic rashes. Symptoms can be either rapid or gradual in onset, possibly occurring over hours to days. Rapid allergic reaction may include anaphylaxis, a potentially life-threatening condition which requires treatment with epinephrine. Other presentations may include atopic dermatitis or inflammation of the esophagus.[10] For food labeling requirements established in many countries, sesame is among the eight common food allergens responsible for 90% of allergic reactions to foods: cow's milk, eggs, wheat, shellfish, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, and soy beans.[11][12]

In addition to water-soluble allergenic proteins, sesame seeds share with peanuts and hazelnuts a class of allegenic proteins known as oleosins. Commercially prepared sesame extracts lack these lipophilic proteins, and so can present false negative skin prick test results even though the oleosins can be responsible for a range of allergic reactions, including anaphylactic shock.[13]

Unlike early childhood allergic reactions to milk and eggs, which often lessen as the children age,[14] sesame allergy persists into older childhood and adulthood, with only an estimated 20-30% of affected people developing tolerance.[4] Strong predictors for adult-persistence are anaphylaxis, high sesame-specific serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) and robust response to the skin prick test. Sesame allergy can be cross-reactive with allergy to peanuts, hazelnuts and almonds.[15]

Signs and symptoms

Food allergies in general usually have a fast onset (from seconds to one hour).[16] Symptoms may include rash, hives, itching of mouth, lips, tongue, throat, eyes, skin, or other areas, swelling of lips, tongue, eyelids, or the whole face, difficulty swallowing, runny or congested nose, hoarse voice, wheezing, shortness of breath, diarrhea, abdominal pain, lightheadedness, fainting, nausea, or vomiting.[16] Symptoms of allergies vary from person to person and incident to incident.[16]

Potentially a life-threatening response, the onset of an allergic reaction occurs when respiratory distress occurs, indicated by wheezing, breathing difficulty, and cyanosis, and circulatory impairment exhibits with a weak pulse, pale skin, and fainting. Such a severe allergic reaction is called anaphylaxis when IgE antibodies are released,[17] and areas of the body not in direct contact with the food show severe symptoms.[16][18] Untreated, the overall response can proceed to vasodilation, a low blood pressure situation called anaphylactic shock.[18] All of these symptoms have been mentioned in descriptions of sesame allergy.[19]

Causes

Eating sesame

The cause is typically the eating of foods containing sesame seeds[4] or sesame seed oil.[13] Briefly, the immune system overreacts to proteins found in sesame-containing foods. Once an allergic reaction has occurred, it remains a lifelong sensitivity for 70-80% of people.[4]

Cross-contact

Cross-contact, also referred to as cross-contamination, occurs when foods are being processed in factories or at food markets, or are being prepared for cooking in restaurants and home kitchens. The allergenic proteins are transferred from one food to another.[20] Bakeries are mentioned as a possible site of cross-contact because sesame seeds are used as ingredients in various baked goods.[21] Assessment of food products purchased from Middle Eastern grocery stores and bakeries in Montreal, Canada found that 16% of packaged products with Precautionary Allergen Labelling may contain sesame; the finding indicates that products had measurable sesame content, causing inadvertent cross-contamination.[22]

Occupational exposure

Exposure of inhaled sesame dust has occurred at bakeries.[1]

Cross-reactivity to other plant foods

The 2S albumins in sesame seeds partially share amino acid sequence and structure with 2S albumins from other plants, and are likely the proteins responsible for cross-reactive allergic reactions to peanuts, almonds, and hazelnuts.[15][23] Allergic reactions to oleosins from hazelnut and peanut oils have been confirmed as cross-reactive to sesame oil.[13] Protein analysis suggests allergy to chia seeds may cross-react with sesame allergy.[24]

Mechanisms

Allergic response

Conditions caused by food allergies are classified into three groups according to the mechanism of the allergic response:[12]

- IgE-mediated (classic) – the most common type, manifesting acute changes that occur shortly after eating, and may progress to anaphylaxis

- Non-IgE mediated – characterized by an immune response not involving immunoglobulin E; may occur hours to days after eating, complicating diagnosis

- IgE and non-IgE-mediated – a hybrid of the above two types

Allergic reactions are hyperactive responses of the immune system to generally innocuous substances, such as food proteins.[25] Why some proteins trigger allergic reactions while others do not is not entirely clear. One theory holds that proteins which resist digestion in the stomach, therefore reaching the small intestine relatively intact, are more likely to be allergenic, but studies have shown that digestion may abolish, decrease, have no effect, or even increase the allergenicity of food allergens.[26] The heat of cooking structurally degrades protein molecules, potentially making them less allergenic.[27][28]

Hypersensitivities are categorized according to the parts of the immune system that are attacked and the amount of time it takes for the response to occur. The four types of hypersensitivity reaction are: type 1, immediate IgE-mediated; type 2, cytotoxic; type 3, immune complex-mediated; and type 4, delayed cell-mediated.[29] The consequent pathophysiology of allergic responses can be divided into two time periods: The first is an acute response that occurs within minutes after exposure to an allergen.[30] This phase can either subside or progress into a "late-phase reaction" which can substantially prolong the symptoms of a response, and result in more tissue damage hours later.[31]

In the early stages of acute allergic reaction, lymphocytes previously sensitized to a specific protein or protein fraction react by quickly producing a particular type of antibody known as secreted IgE (sIgE), which circulates in the blood and binds to IgE-specific receptors on the surface of other kinds of immune cells called mast cells and basophils. Both of these are involved in the acute inflammatory response.[30] Activated mast cells and basophils undergo a process called degranulation, during which they release histamine and other inflammatory chemical mediators called (cytokines, interleukins, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins) into the surrounding tissue causing several systemic effects, such as vasodilation, mucous secretion, nerve stimulation, and smooth-muscle contraction.[30] This results in runny nose, itchiness, shortness of breath, and potentially anaphylaxis.[30] Depending on the individual, the allergen, and the mode of introduction, the symptoms can be system-wide (classical anaphylaxis), or localized to particular body systems; asthma is localized to the respiratory system while hives and eczema are localized to the skin.[30] In addition to reacting to oral consumption, skin reactions can be triggered by contact if there are skin abrasions or cuts.

After the chemical mediators of the acute response subside, late-phase responses can often occur due to the migration of other white blood cells such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and macrophages to the initial reaction sites. This is usually seen 2–24 hours after the original reaction.[31] Cytokines from mast cells may also play a role in the persistence of long-term effects. Late-phase responses seen in asthma are slightly different from those seen in other allergic responses, although they are still caused by release of mediators from eosinophils.[32][33]

Sesame allergenic proteins

Eight sesame seed allergens have been characterized (Ses i 1 to Ses i 8). Ses i 1 and Ses i 2 are of the biochemical type 2S albumins; these partially share amino acid sequence and structure with 2S albumins from other plants, and are likely the proteins responsible for cross-reactive allergic reactions to peanuts and certain tree nuts: almonds and hazelnuts.[15] Ses i 3 is a vivilin-like globulin. Ses i 4 and Ses i 5 are oleosins, associated with oil bodies, which appear to contribute to cross-reactivity to hazelnut and peanut oils.[1] Ses i 6 and Ses i 7 are globulins. Ses i 8 is a profilin.[1][34]

Allergic reactions to oleosins from sesame, hazelnut and peanut oils have been confirmed, ranging from contact dermatitis to anaphylactic shock.[13][35][36] The sesame oil body associated proteins are at ~17 and ~15 kDa, named, respectively, Ses i 4 and Ses i 5.[1][35] Standardized sesame extracts used for allergy diagnosis do not contain oleosins, so the results of skin prick tests can present a false negative whereas using freshly ground seeds eliciting a true positive.[13] Commercial-grade peanut oil is highly refined, so the oleosins are removed, but commercial-grade sesame oil intended for food consumption is typically an unrefined product with a measurable protein content.[36]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on a medical history, elimination diet, skin prick test, blood tests for food-specific IgE antibodies, or oral food challenge.[37] However, standardized sesame extracts used for allergy diagnosis do not contain oleosins, so the results of skin prick tests can present a false negative whereas using freshly ground seeds eliciting a true positive.[13] Confirmation is by double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges, which remains the "diagnostic gold standard" for sesame allergy.[4] Self-reported sesame allergy often fails to be confirmed by food challenge.[3]

Prevention

Reviews of food allergens in general stated that introducing solid foods at 4–6 months may result in the lowest subsequent allergy risks for exzema, allergic rhinitis and more severe reactions, with the best evidence for peanuts and chicken eggs.[38][39] As of March 2022, one clinical trial attempted to determine whether introducing sesame to the diets of infants early or delaying until older would affect the risk of subsequent allergy, but there were too few confirmed subsequent sesame allergy subjects in the test or control groups to conduct a statistical analysis.[39]

Foods to avoid

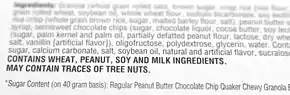

The countries making up the European Union require packaged food labeling for sesame.[7] US labels will comply after January 1, 2023.[6] A wide variety of foods may contain whole sesame seeds, seeds ground to a powder, and/or sesame oil. Traditional food recipes from the Middle East and Asia, including tahini, tempeh, baklava, hummus, baba ghanoush and halva, plus granola-type food bars, frequently contain sesame. Baked goods such as bagels may have whole sesame seeds as topping. In Japan, hard candies and snack bars often contain whole sesame seeds. People with a known sesame allergy should make that information clear to staff when dining at restarurants. In addition, cosmetics, dietary supplements and drug products may contain sesame oil.[1][19]

Treatment

Treatment for accidental ingestion of sesame products by allergic individuals varies depending on the sensitivity of the person. An antihistamine such as diphenhydramine may be prescribed. Sometimes prednisone will be prescribed to prevent a possible late phase Type I hypersensitivity reaction.[40] Severe allergic reactions (anaphalaxis) may require treatment with an epinephrine pen, which is an injection device designed to be used by a non-healthcare professional when emergency treatment is warranted.[41] Unlike for egg allergy, for which there is active research on trying oral immunotherapy (OIT) to desensitize people to egg allergens,[42] oral immunotherapy for sesame allergy has not reached the quality of evidence that would support this as a medical treatment.[1][4]

Prognosis

Unlike milk and egg allergies,[14][43] 70-80% of sesame allergy cases persist into adulthood.[4]

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence are terms commonly used in describing disease epidemiology. Incidence is newly diagnosed cases, which can be expressed as new cases per year per million people. Prevalence is the number of cases alive, expressible as existing cases per million people during a period of time.[44] Sesame allergy is a common food allergy, with prevalence estimates in the range of 0.1-0.2% of the population,[1][2][3][4] and confirmed as high as 0.8-0.9% in the Middle East and other countries where sesame seeds are used in traditional foods.[4][34] Reporting of sesame seed allergy has increased over recent decades, either a true increase due to exposure from more foods or an increase in awareness.[1][2][5] Self-reported allergy prevalence is always higher than food-challenge confirmed allergy. One review of US data reported 0.49% for the former and 0.23% for the latter.[3]

Society and culture

Whether food allergy prevalence is increasing or not, food allergy awareness has increased, with impacts on the quality of life for children, their parents and their immediate caregivers.[45][46][47][48] In the United States, the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act (FALCPA) of 2004 causes people to be reminded of allergy problems every time they handle a food package. Although not regulated under FALCPA, restaurants have added allergen warnings to menus. The Culinary Institute of America, a premier school for chef training, has courses in allergen-free cooking and a separate teaching kitchen.[49] School systems have protocols about what foods can be brought into the school. Despite all these precautions, people with serious allergies are aware that accidental exposure can easily occur at other peoples' houses, at school or in restaurants.[50] Food fear has a significant impact on quality of life.[47][48]

Regulation of labelling

In response to the risk that certain foods pose to those with food allergies, some countries have responded by instituting labeling laws that require food products to clearly inform consumers if their products contain major allergens or byproducts of major allergens among the ingredients intentionally added to foods. Laws and regulations passed in the US and by the European Union recommend labeling but do not require mandatory declaration of the presence of trace amounts in the final product as a consequence of unintentional cross-contamination.[7][51][52]

Ingredients intentionally added

FALCPA became effective 1 January 2006, requiring companies selling foods in the United States to disclose on labels whether a packaged food product contains any of these eight major food allergens, added intentionally: cow's milk, peanuts, eggs, shellfish, fish, tree nuts, soy and wheat.[51][53] This list originated in 1999 from the World Health Organisation Codex Alimentarius Commission.[54] To meet FALCPA labeling requirements, if an ingredient is derived from one of the required-label allergens, then it must either have its "food sourced name" in parentheses, for example "Casein (milk)," or as an alternative, there must be a statement separate but adjacent to the ingredients list: "Contains milk" (and any other of the allergens with mandatory labeling).[51][52]

November 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issed draft guidance recommending that food manufacturers add sesame-containing foods to labels.[55] The "FASTER Act" was passed in April 2021, stipulating that labeling be mandatory,[6] to be in effect January 1, 2023, making it the ninth required food ingredient label in the US.[56][57]

FALCPA applies to packaged foods regulated by the FDA, which does not include poultry, most meats, certain egg products, and most alcoholic beverages.[53] Some meat, poultry, and egg processed products may contain allergenic ingredients. These products are regulated by the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), which requires that any ingredient be declared in the labeling only by its common or usual name. Neither the identification of the source of a specific ingredient in a parenthetical statement nor the use of statements to alert for the presence of specific ingredients, like "Contains: milk", are mandatory according to FSIS.[58] FALCPA also does not apply to food prepared in restaurants.[59][60] In contrast, the EU Food Information for Consumers Regulation 1169/2011 requires food businesses to provide allergy information on food sold unpackaged.[61] Examples would include by catering outlets and deli counters, bakeries and sandwich bars.[62]

The European Union requires listing for those eight major allergens plus molluscs, celery, mustard, lupin, sesame and sulfites.[7] In Japan, a food-labeling system for five specific allergenic ingredients (egg, milk, wheat, buckwheat, peanut) was mandated under law on April 1, 2002, adding shrimp/prawn and crab in 2008. Walnut was added in 2019. Sesame is on a list of 27 foods for which labeling is recommended but remains voluntary.[8] Labeling requirements apply to packaged food, but not to restaurants.[63]

See also

- List of allergens (food and non-food)

References

- Patel A, Bahna SL (October 2016). "Hypersensitivities to sesame and other common edible seeds". Allergy. 71 (10): 1405–13. doi:10.1111/all.12962. PMID 27332789. S2CID 13026863.

- Dalal I, Goldberg M, Katz Y (August 2012). "Sesame seed food allergy". Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 12 (4): 339–45. doi:10.1007/s11882-012-0267-2. PMID 22610362. S2CID 11111725.

- Warren CM, Chadha AS, Sicherer SH, Jiang J, Gupta RS (August 2019). "Prevalence and Severity of Sesame Allergy in the United States". JAMA Netw Open. 2 (8): e199144. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9144. PMC 6681546. PMID 31373655.

- Adatia A, Clarke AE, Yanishevsky Y, Ben-Shoshan M (April 2017). "Sesame allergy: current perspectives". J Asthma Allergy. 10: 141–51. doi:10.2147/JAA.S113612. PMC 5414576. PMID 28490893.

- Gangur V, Kelly C, Navuluri L (July 2005). "Sesame allergy: a growing food allergy of global proportions?". Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 95 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61181-7. PMID 16095135.

- "Food Allergy Safety, Treatment, Education, and Research Act of 2021 or the FASTER Act of 2021". Congress.gov. 4 April 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "Regulation (EG) 1169/2011 (Annex II)". Eur-Lex - European Union Law, European Union. 25 October 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ""Almond" is added to the list of foods recommended to use allergens labeling and "walnut" is changed from recommended to mandatory". Label Bank. September 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- Taylor SL, Baumert JL (2015). "Worldwide food allergy labeling and detection of allergens in processed foods". Chem Immunol Allergy. Chemical Immunology and Allergy. 101: 227–34. doi:10.1159/000373910. ISBN 978-3-318-02340-4. PMID 26022883.

- National Report of the Expert Panel on Food Allergy Research, NIH-NIAID 2003 "National Report of the Expert Panel on Food Allergy Research" (PDF). 30 June 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

- "Food Allergies" Archived 2012-10-06 at the Wayback Machine Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America

- "Food allergy". National Health Service (England). 16 May 2016. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Jappe U, Schwager C (August 2017). "Relevance of Lipophilic Allergens in Food Allergy Diagnosis". Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 17 (9): 61. doi:10.1007/s11882-017-0731-0. PMID 28795292. S2CID 562068.

- Urisu A, Ebisawa M, Ito K, Aihara Y, Ito S, Mayumi M, Kohno Y, Kondo N (September 2014). "Japanese Guideline for Food Allergy 2014". Allergol Int. 63 (3): 399–419. doi:10.2332/allergolint.14-RAI-0770. PMID 25178179.

- Dreskin SC, Koppelman SJ, Andorf S, Nadeau KC, Kalra A, Braun W, Negi SS, Chen X, Schein CH (April 2021). "The importance of the 2S albumins for allergenicity and cross-reactivity of peanuts, tree nuts, and sesame seeds". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 147 (4): 1154–63. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.11.004. PMC 8035160. PMID 33217410.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Food allergy

- Reber, Laurent L.; Hernandez, Joseph D.; Galli, Stephen J. (August 2017). "The pathophysiology of anaphylaxis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 140 (2): 335–348. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.003. ISSN 0091-6749. PMC 5657389. PMID 28780941.

- Sicherer SH, Sampson HA (February 2014). "Food allergy: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 133 (2): 291–307. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.020. PMID 24388012.

- "Foods to avoid with a sesame allergy". Medical News Today. 27 July 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- "Avoiding Cross-Contact". FARE: Food Allergy Research & Education. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "Sesame". Food Allergy Canada. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- Touma J, La Vieille S, Guillier L, Barrere V, Manny E, Théolier J, Dominguez S, Godefroy SB (April 2021). "Occurrence and risk assessment of sesame as an allergen in selected Middle Eastern foods available in Montreal, Canada". Food Addit Contam Part a Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 38 (4): 550–62. doi:10.1080/19440049.2021.1881622. PMID 33667147. S2CID 232129473.

- Stutius LM, Sheehan WJ, Rangsithienchai P, Bharmanee A, Scott JE, Young MC, Dioun AF, Schneider LC, Phipatanakul W (December 2010). "Characterizing the relationship between sesame, coconut, and nut allergy in children". Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 21 (8): 1114–18. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.00997.x. PMC 2987573. PMID 21073539.

- Albunni BA, Wessels H, Paschke-Kratzin A, Fischer M (July 2019). "Antibody Cross-Reactivity between Proteins of Chia Seed ( Salvia hispanica L.) and Other Food Allergens". J Agric Food Chem. 67 (26): 7475–84. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.9b00875. PMID 31117490. S2CID 162181417.

- McConnell, Thomas H. (2007). The Nature of Disease: Pathology for the Health Professions. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7817-5317-3. Archived from the original on 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- Bøgh KL, Madsen CB (July 2016). "Food Allergens: Is There a Correlation between Stability to Digestion and Allergenicity?". Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 56 (9): 1545–67. doi:10.1080/10408398.2013.779569. PMID 25607526. S2CID 205691620.

- Davis PJ, Williams SC (1998). "Protein modification by thermal processing". Allergy. 53 (46 Suppl): 102–5. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb04975.x. PMID 9826012. S2CID 10621652.

- Verhoeckx KC, Vissers YM, Baumert JL, Faludi R, Feys M, et al. (June 2015). "Food processing and allergenicity". Food Chem Toxicol. 80: 223–40. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2015.03.005. PMID 25778347.

- Nester, Eugene W.; Anderson, Denise G.; Roberts Jr, C. Evans; Nester, Martha T. (2009). "Immunologic Disorders". Microbiology: A Human Perspective (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 414–28.

- Janeway, Charles; Paul Travers; Mark Walport; Mark Shlomchik (2001). Immunobiology; Fifth Edition. New York and London: Garland Science. pp. e–book. ISBN 978-0-8153-4101-7. Archived from the original on 2009-06-28.

- Grimbaldeston MA, Metz M, Yu M, Tsai M, Galli SJ (December 2006). "Effector and potential immunoregulatory roles of mast cells in IgE-associated acquired immune responses". Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18 (6): 751–60. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2006.09.011. PMID 17011762.

- Holt PG, Sly PD (October 2007). "Th2 cytokines in the asthma late-phase response". Lancet. 370 (9596): 1396–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61587-6. PMID 17950849. S2CID 40819814.

- Ho MH, Wong WH, Chang C (June 2014). "Clinical spectrum of food allergies: a comprehensive review". Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 46 (3): 225–40. doi:10.1007/s12016-012-8339-6. PMID 23229594. S2CID 5421783.

- "Improved sesame allergy diagnosis with Ses i 1" (PDF). ThermoScientific. 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Zuidmeer-Jongejan L, Fernández-Rivas M, Winter MG, Akkerdaas JH, Summers C, et al. (February 2014). "Oil body-associated hazelnut allergens including oleosins are underrepresented in diagnostic extracts but associated with severe symptoms". Clin Transl Allergy. 4 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/2045-7022-4-4. PMC 4015814. PMID 24484687.

- Alonzi C, Campi P, Gaeta F, Pineda F, Romano A (June 2011). "Diagnosing IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to sesame by an immediate-reading "contact test" with sesame oil". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 127 (6): 1627–29. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.050. PMID 21377720.

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (July 2012). "Food Allergy An Overview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05.

- Ferraro V, Zanconato S, Carraro S (May 2019). "Timing of Food Introduction and the Risk of Food Allergy". Nutrients. 11 (5): 1131. doi:10.3390/nu11051131. PMC 6567868. PMID 31117223.

- Perkin MR, Logan K, Bahnson HT, Marrs T, Radulovic S, Craven J, et al. (December 2019). "Efficacy of the Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study among infants at high risk of developing food allergy". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 144 (6): 1606–14.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.045. PMC 6902243. PMID 31812184.

- Tang AW (October 2003). "A practical guide to anaphylaxis". Am Fam Physician. 68 (7): 1325–32. PMID 14567487.

- The EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group (August 2014). "Anaphylaxis: guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology". Allergy. 69 (8): 1026–45. doi:10.1111/all.12437. PMID 24909803. S2CID 11054771.

- Romantsik, O; Tosca, MA; Zappettini, S; Calevo, MG (April 2018). "Oral and sublingual immunotherapy for egg allergy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (4): CD010638. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010638.pub3. PMC 6494514. PMID 29676439.

- Savage J, Johns CB (February 2015). "Food allergy: epidemiology and natural history". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 35 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2014.09.004. PMC 4254585. PMID 25459576.

- "What is Prevalence?" Archived 2020-12-26 at the Wayback Machine National Institute of Mental Health (Accessed 25 December 2020).

- Ravid NL, Annunziato RA, Ambrose MA, Chuang K, Mullarkey C, Sicherer SH, Shemesh E, Cox AL (March 2015). "Mental health and quality-of-life concerns related to the burden of food allergy". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 38 (1): 77–89. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2014.11.004. PMID 25725570.

- Morou Z, Tatsioni A, Dimoliatis ID, Papadopoulos NG (June 2014). "Health-related quality of life in children with food allergy and their parents: a systematic review of the literature". J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 24 (6): 382–95. PMID 25668890.

- Lange L (November 2014). "Quality of life in the setting of anaphylaxis and food allergy". Allergo J Int. 23 (7): 252–60. doi:10.1007/s40629-014-0029-x. PMC 4479473. PMID 26120535.

- van der Velde JL, Dubois AE, Flokstra-de Blok BM (December 2013). "Food allergy and quality of life: what have we learned?". Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 13 (6): 651–61. doi:10.1007/s11882-013-0391-7. PMID 24122150. S2CID 326837.

- Culinary Institute of America Archived 2017-11-10 at the Wayback Machine Allergen-free oasis comes to the CIA (2017)

- Shah E, Pongracic J (August 2008). "Food-induced anaphylaxis: who, what, why, and where?". Pediatr Ann. 37 (8): 536–41. doi:10.3928/00904481-20080801-06. PMID 18751571.

- "Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004". FDA. 2 August 2004. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- FDA (December 2017). "Have Food Allergies? Read the Label". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- FDA (2021). "Food Allergies: What You Need to Know". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- Allen KJ, Turner PJ, Pawankar R, Taylor S, Sicherer S, Lack G, et al. (April 2014). "Precautionary labelling of foods for allergen content: are we ready for a global framework?". World Allergy Organ J. 7 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/1939-4551-7-10. PMC 4005619. PMID 24791183.

- "FDA Encourages Manufacturers to Clearly Declare All Uses of Sesame in Ingredient List on Food Labels". Food and Drug Administration. 10 November 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "Sesame Allergy". FARE. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "Sesame Allergy and Food Labels". Allergy & Asthma Network. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "FSIS Compliance Guidelines Allergens and Ingredients of Public Health Concern: Identification, Prevention and Control, and Declaration through Labeling" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service. November 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- Roses JB (February 2011). "Food allergen law and the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004: falling short of true protection for food allergy sufferers". Food Drug Law J. 66 (2): 225–42, ii. PMID 24505841.

- FDA (July 2006). "Food Allergen Labeling And Consumer Protection Act of 2004 Questions and Answers". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "EU law on food information to consumers". European Commission. 17 October 2016. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- "Allergy and intolerance: guidance for businesses". Archived from the original on 2014-12-08. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- Akiyama H, Imai T, Ebisawa M (2011). "Chapter 4: Japan Food Allergen Labeling Regulation—History and Evaluation". Advances in Food and Nutrition Research. 62: 139–71. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385989-1.00004-1. PMID 21504823. Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2021-05-03.