Italy–Spain relations

Italy–Spain relations refers to interstate relations between Italy and Spain. Both countries established diplomatic relations some time after the unification of Italy in 1860.

| |

Italy |

Spain |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Italy, Madrid | Embassy of Spain, Rome |

Precedents

In 218 BC the Romans conquered the Iberian Peninsula, which later became the Roman province of Hispania. The Romans introduced the Latin language, the ancestor of both modern-day Italian and Spanish. The Iberian Peninsula remained under Roman rule for over 600 years, until the decline of the Western Roman Empire. In the Early modern period, until the 18th century, southern and insular Italy came under Spanish control, having been previously a domain of the Crown of Aragon.

Establishment of diplomatic relations

After the proclamation of Victor Emmanuel II as King of Italy in 1861 Spain failed to initially recognise the country, still considering Victor Emmanuel as the "Sardinian King".[1] The recognition was met by the opposition of Queen Isabella II of Spain, influenced by the stance of Pope Pius IX.[2] Once Leopoldo O'Donnell overcame the opposition of the Queen, Spain finally recognised the Kingdom of Italy on 15 July 1865.[3] Soon later, in 1870, following the dethronement of Isabella II at the 1868 Glorious Revolution, the second son of Victor Emmanuel II, Amadeo I, was elected King of Spain, reigning from 1871 until his abdication in 1873.

Situation after World War I

Despite some incipient attempts to promote further understanding between the two countries, immediately after the end of World War I there were still issues restraining further Italian-Spanish engagement in Spain, including a sector of public opinion showing aversion towards Italy (a prominent example being Austria-born Queen Mother Maria Christina).[4]

Rapprochement between the Mediterranean dictatorships

Once dictators Benito Mussolini (1922) and Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923) got to power, conditions for closer relations became more clear, with the notion of a rapprochement to Italy becoming more interesting to the Spanish Government policy, particularly in terms of the profit those improved relations could deliver to Spain vis-à-vis the Tangier question.[4] For Italy, the installment of the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera offered a prospect for greater ascendancy over a country with a government now widely interested in the reforms carried out in Fascist Italy.[5] Relations during this period were often embedded in a diplomatic triangle between France, Italy and Spain. While showing a will for friendship and rapprochement, the "Treaty for Conciliation and Arbitration" signed in August 1926 between the two countries delivered limited substance in practical terms, compared to the expectations at the starting point of the Primorriverista dictatorship.[6]

A diplomatic "honeymoon" between the two regimes followed the signing of the treaty, nonetheless.[7]

Conspirations against the Spanish Republic

The early monarchist conspirations against the Second Spanish Republic enjoyed support from Mussolini.[8] One of the most important Italian communities in Spain resided in Catalonia as well as the Italian economic interests in Spain lied there, hence that region became a significant point of attention for the Italian diplomacy during the Spanish Second Republic, and the Italian diplomacy established some contacts with incipient philo-fascist elements within Republican Left of Catalonia, including Josep Dencàs, although Italy eventually went on to bet on Spanish fascism.[9] Although both monarchists from Renovación Española, the traditionalists and the Fascist falangists engaged in negotiations asking help from Fascist Italy regarding the preparations of the 1936 coup d'état, Mussolini decided not to take part at the time.[8]

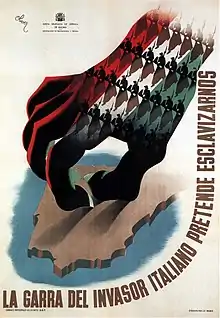

Italian intervention in the Spanish Civil War

After 18 July 1936 and the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, Mussolini changed the strategy and intervened on the side of the Rebel faction.[8] The Corps of Volunteer Troops (CTV), a fascist expeditionary force from Italy, brought in about 78,000 Italian troops, sent to help Franco and vowing to establish a Fascist Spain and a Fascist Europe.[10] Key military actions in which the CTV took part include Málaga, Bermeo, Santander and the March 1937 fiasco of Guadalajara.[11]

Italian submarines carried out a campaign against Republican ships, also targeting Mediterranean ports together with surface ships.[12] The Italian Regia Marina also provided key logistical support to the Rebels, including escort of commercial shipment transporting war supplies,[13] and, seeking to facilitate the naval blockade on the Republic, it also allowed the Rebel Navy the use of anchorages in Sicily and Sardinia.[14]

Italians forces partially occupied the Balearic Islands and soon established an air base of the Aviazione Legionaria in Mallorca, from which Italians were given permission by the rebel authorities to bomb locations across the Peninsular Levante controlled by the Republic (including the bombings of Barcelona investigated as crimes against humanity).[15] A Fascist squadristi, Arconovaldo Bonaccorsi, led a wild repression in the Balearic islands.[16]

World War II

During World War II, 1939 to 1943, Spanish-Italian ties were close. Though Italy fought alongside Germany during the war, Spain was recovering from a civil war and remained neutral. In February 1941, the meeting between Mussolini and Franco in Bordighera took place; during the meeting the Duce asked Franco to join the Axis.[17]

The fall of Mussolini came as a shock to the Franco administration. During first few weeks the tightly-censored Spanish press limited themselves to laconic, matter-of-fact information when providing news on the Italian developments.[18] However, after the Italian-American armistice had been made public, the Spanish papers extensively quoted the official German statement, which lambasted the Italian treason. Some Spanish officers sent their Italian military condecorations back to the Italian embassy in Madrid.[19]

Since mid-September 1943 two shadowy Italian states, the one headed by Mussolini and the one headed by king Victor Emmanuel III, competed for Spanish diplomatic recognition; the German diplomatic representatives in Madrid pressed the case of Mussolini, the Allied ones advised strongly against it.[20] Following a period of hesitation, in late September Spain declared it would continue its official relations with the Kingdom of Italy.[21]

The Italian embassador in Madrid Paulucci di Calboli opted for the Badoglio government, even though some Italian consuls in Spain declared loyalty to Mussolini.[22] The Spanish embassador in Fascist Italy, Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta, formally remained at the post of the Spanish representative in the Kingdom, though he returned to Madrid; in practice before the Badoglio administration Spain was represented by lower-rank officials.[23] However, Spain maintained informal relations with Repubblica Sociale Italiana. The former Italian consul in Málaga, Eugenio Morreale, became an unofficial Mussolini representative in Madrid;[24] the Spanish consul in Milan, Fernando Chantel, became an unofficial Franco representative in RSI.[25]

In practice, Spain maintained distance towards both the so-called Kingdom of the South and the RSI. Badoglio sought Madrid's good offices to expedite negotiations with the Allies, but he was turned down. However, also major Fascist figures who sought Spanish passports were almost always denied assistance.[26] During final months of the war new embassadors were appointed by both Spain (José Antonio de Sangróniz y Castro) and the Kingdom of Italy (Tommaso Gallarati Scotti), though Sangróniz arrived no earlier than in May 1945.[27]

Common membership

Nowadays, Italy and Spain are full member countries of the European Union, the NATO and the Union for the Mediterranean.

Resident diplomatic missions

- Italy has an embassy in Madrid and a consulate-general in Barcelona.

- Spain has an embassy in Rome and consulates-general in Milan and Naples.

_01b.jpg.webp) Embassy of Italy in Madrid

Embassy of Italy in Madrid Consulate-General of Italy in Barcelona

Consulate-General of Italy in Barcelona Embassy of Spain in Rome

Embassy of Spain in Rome Building hosting the Consulate-General of Spain in Milan

Building hosting the Consulate-General of Spain in Milan

See also

References

- López Vega & Martínez Neira 2011, p. 96.

- López Vega & Martínez Neira 2011, pp. 96, 98.

- López Vega & Martínez Neira 2011, p. 99.

- Sueiro Seoane 1987, pp. 185–186.

- Domínguez Méndez 2013, p. 238.

- Tusell & Saz 1982, pp. 443–445.

- Tusell & Saz 1982, p. 444.

- Saz-Campos 1981, p. 321.

- González i Vilalta 2009, pp. 11–12.

- Rodrigo 2019, pp. 86–87.

- Rodrigo 2019, pp. 87, 91.

- Campo Rizo 1997, pp. 75–77.

- Campo Rizo 1997, pp. 70–71.

- Campo Rizo 1997, p. 73.

- Aguilera Povedano 2019, pp. 285–286.

- Aguilera Povedano 2019, p. 291.

- Payne 1998, p. 110.

- Eszter Katona, Relaciones ítalo-españolas en el periodo 1943-1945, [in:] Antoni Segura, Andreu Mayayo, Teresa Abelló (eds.), La dictadura franquista. La institucionalització d’un régim, Barcelona 2012, ISBN 9788491687139, p. 672

- Katona 2012, p. 675

- Katona 2012, pp. 676-678

- Katona 2012, p. 677

- those in Barcelona, Málaga and Tetuan. Consuls in San Sebastián and Sevilla opted for Badoglio, Katona 2012, pp. 678-679

- Katona 2012, pp. 680-681

- Katona 2012, p. 679

- Katona 2012, p. 681

- Payne 1998, p. 112.

- Katona 2012, p. 682

Bibliography

- Aguilera Povedano, Manuel (2019). "Italia en la Guerra Civil Española: el capitán Villegas y el origen de la Aviación Legionaria de Baleares". Cuadernos de Historia Contemporánea. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense. 41: 285–304. doi:10.5209/chco.66105. ISSN 0214-400X.

- Albanese, Matteo, and Pablo Del Hierro. Transnational fascism in the twentieth century: Spain, Italy and the global neo-fascist network (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016).

- Campo Rizo, José Manuel (1997). "El Mediterráneo, campo de batalla de la Guerra Civil española: la intervención naval italiana. Una primera aproximación documental". Cuadernos de Historia Contemporánea. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense. 19: 55–87. ISSN 0214-400X.

- Dandelet, Thomas, and John Marino, eds. Spain in Italy: Politics, Society, and Religion 1500-1700 (Brill, 2006).

- Domínguez Méndez, Rubén (2013). "Francia en el horizonte. La política de aproximación italiana a la España de Primo de Rivera a través del campo cultural". Memoria y Civilización. Pamplona: University of Navarre (16): 237–265.

- González i Vilalta, Arnau (2009). Cataluña bajo vigilancia: El consulado italiano y el fascio de Barcelona (1930-1943). Valencia: Publicacions de la Universitat de València. ISBN 978-84-370-8309-4.

- Hierro Lecea, Pablo del (2015). Spanish-Italian Relations and the Influence of the Major Powers, 1943-1957. Security, Conflict and Cooperation in the Contemporary World. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-49654-9.

- López Vega, Antonio; Martínez Neira, Manuel (2011). "España y la(s) cuestión(es) de Italia" (PDF). Giornale di Storia Costituzionale (22): 96.

- Payne, Stanley G. (1998). "Fascist Italy and Spain, 1922–45" (PDF). Mediterranean Historical Review. 13 (1–2): 99–115. doi:10.1080/09518969808569738. ISSN 0951-8967.

- Rodrigo, Javier (2019). "A fascist warfare? Italian fascism and war experience in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39)". War in History. 26 (1): 86–104. doi:10.1177/0968344517696526. S2CID 159711547.

- Saz-Campos, Ismael (1981). "De la conspiración al alzamiento. Mussolini y el alzamiento nacional" (PDF). Cuadernos de trabajos de la Escuela Española de Historia y Arqueología en Roma: 321–358. ISSN 0392-0801.

- Sueiro Seoane, Susana (1987). "La política mediterránea de Primo de Rivera: el triángulo Hispano-ltalo-Francés" (PDF). Revista de la Facultad de Geografía e Historia. Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (1): 183–223.

- Tusell, Javier; Saz, Ismael (1982). "Mussolini y Primo de Rivera: las relaciones políticas y económicas de dos dictaturas mediterráneas". Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. CLXXIX (III): 413–484.

.svg.png.webp)