Apocalypse of Paul

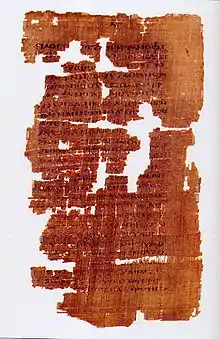

The Apocalypse of Paul (Apocalypsis Pauli, more commonly known in the Latin tradition as the Visio Pauli or Visio sancti Pauli) is a fourth-century non-canonical apocalypse and part of the New Testament apocrypha. The full original Greek version of the Apocalypse is lost, although fragmentary versions still exist. Using later versions and translations, the text has been reconstructed, notably from Latin and Syriac translations. The text is not to be confused with the gnostic Coptic Apocalypse of Paul, which is unlikely to be related.

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

The text, which is pseudepigraphal, purports to present a detailed account of a vision of Heaven and Hell experienced by Paul the Apostle. While the work was not accepted among the Church leaders, it helped to shape the beliefs of many Christians concerning the nature of the afterlife. At the end of the text, Paul or the Virgin Mary (depending on the manuscript) manages to persuade God to give everyone in Hell a day off every Sunday.

Authorship and date

The book opens with a discovery narrative that explains that while the Apostle Paul wrote it, the book was then buried beneath the foundations of a house in Tarsus for centuries until an angel ordered the compiler to dig it up. The book claims this discovery happened during the reign of Emperor Theodosius I (reigned 379–395), giving a good estimate of roughly when the narrative appeared. (The Christian author Sozomen wrote that he investigated this claim, and an elderly priest of Tarsus had no recollection of such a bizarre event occurring; rather, it was transparently an attempt to explain how a "new" work of Paul could be published.)

Kirsti Copeland argues that the Apocalypse of Paul was composed at a communal Pachomian monastery in Egypt between 388-400 CE.[1] Bart Ehrman also dates it to the late 4th century.[2][3] The text had to exist by 415, as Augustine makes a disparaging comment about it in his Tractates on the Gospel of John.[4][5]

Content

The text is primarily focused on a detailed account of Heaven and Hell. The author seems to be familiar with the "Book of the Watchers" in the Book of Enoch, the Apocalypse of Zephaniah, and the Apocalypse of Peter as influences on the work. Nevertheless, the accounts of Heaven and Hell in the Apocalypse of Paul differ from its predecessors in some major ways. The Apocalypse of Peter was written during a period when Christians were a minority struggling to gain adherents, and tensions with pagans and Jews were a major issue. The Apocalypse of Paul was written much later when Christianity had become the accepted and majority religion of the Roman Empire. As such, much of its focus is not on external issues, but rather issues internal to Christianity. More devout and ascetic Christians will be rewarded additionally in heaven beyond what is given to more passive Christians; Christians who err in some manner, whether by heresy, or a failure to uphold ascetic vows, will be condemned to hell. The text gives little to no discussion to non-Christians, seemingly considering them irrelevant; its Hell is one of punishment for faulty Christians.[4]

The text is heavily moralistic, and considers pride the root of all evil and the worst sin. It also describes and names various fallen angels in hell, including Temeluchus and the tartaruchi.

Structure

The chapters of the text are roughly organized as:

- 1, 2. Discovery of the revelation.

- 3–6. Prologue: Appeal of creation to God against the sin of man

- 7–10. The report of the angels to God about men.

- 11–18. Deaths and judgements of the righteous and the wicked.

- 19–30. First vision of Paradise, including lake Acherusa.

- 31–44. Hell. Paul obtains rest on Sunday for the lost.

- 45–51. Second vision of Paradise.

Heaven and hell

The Apocalypse of Paul goes into considerably more detail than the Apocalypse of Peter on the nature of heaven. In chapters 20–30, heaven has three divisions. "Paradise" is the third heaven is where Paul arrives first, but it is not closely described. Paul then descends into the second heaven afterward, the "Land of Promise", a reinterpretation of the "land of milk and honey" which is seemingly a holding area for deceased saints who are waiting on the Second Coming of Jesus and the millennial kingdom of God. The first heaven, across the Acherusian Lake, is the "City of Christ" where the blessed will reside for eternity, presumably after the millennial age. Paul does find some dwelling in the City already, such as the Biblical prophets of Judaism and the patriarchs of the twelve tribes. Outside the city are ascetics who were too proud of their asceticism, and are forced to wait for entry until Christ returns and their pride is appropriately chastened. The city itself is subdivided into twelve layers, with things becoming continually better and better the closer to the center inhabitants get. Those who deny themselves physical pleasure in the mortal world are rewarded wildly in the afterlife with better places in the City of Christ, closer to the center. Finally, after the tour of hell, Paul returns to "Paradise" in chapters 45–51, but it is unclear if this means the third layer again, heaven in general, or a new fourth layer. There Paul meets other Biblical figures, some of which were described as already being in other layers in the earlier passages. It is possible that this account was originally from a separate story that was combined into the Apocalypse of Paul, as it does not entirely cohere with the earlier vision of Heaven.[4]

In hell, those punished are Christians who have erred. While some "usual" sins such as usury, adultery, and women having sex before marriage are condemned, the Apocalypse of Paul goes beyond this. Various "bad" Christians are made to stand in a river of fire, including Christians who left the church and argued; Christians who took the Eucharist but then fornicated; and Christians who "slandered" other Christians while in church. Christians who failed to pay attention as the word of God was read in Church are forced to gnaw on their tongues eternally. Christians who commit infanticide are torn to shreds by beasts eternally while also on fire. Church leaders and theologians who preached incorrect doctrine or were simply incompetent in their positions are punished with torture. For example, a church reader who failed to implement the word of God he read during church services in his own life is thrown into a river of fire while an angel slashes his lips and tongue with a razor. Unholy nuns are thrown into a furnace of fire along with a bishop as punishment (in one Latin manuscript, likely a later addition). Failed ascetics are also punished; those who ended their fasts before their appointed time are taunted by abundant food and water just out of reach as they lie parched and starving in hell. Those who wore the habit of a monk or nun while failing to show charity are given new habits of pitch and sulphur, serpents are wrapped around their necks, and fiery angels physically beat them. The worst punishments ("seven times worse" than those described so far) are reserved for theologically deviant Christians, such as those who believe that Jesus's Second Coming will be a "spiritual" resurrection rather than a "physical" resurrection, or who deny that Jesus came in the flesh (docetism). The exact nature of their punishment is left to the imagination; an awful stench rises from a sealed well that hints of their torment below.[4]

One theological oddity is that the text portrays Christians, the angels, and Paul as more merciful than God. Paul expresses pity for those suffering in Hell, but Jesus rebukes him and says that everyone in Hell truly deserves their punishment. The Archangel Michael says he prays continuously for Christians while they are alive, and weeps for the torments the failed Christians endure after it is too late. The twenty-four elders on thrones (presumably the 12 apostles and the 12 patriarchs) as well as the four beasts described in God's throne room in the Book of Revelation also make intercession for the inhabitants of hell. The Christian friends and family of those in Hell also make prayers for the dead that their suffering might be lessened. In responses to the pleas of Paul, Michael, the elders, and the living Christians on Earth, Jesus agrees to release those in hell from their suffering on the day of his resurrection—presumably every Sunday. (A Coptic manuscript instead describes it as specifically Easter, albeit with a 50-day period afterward).[4]

Sozomen wrote that the text was popular with monks, which makes sense given the work's sharp focus on them and how their fates differ from ordinary Christians. Those who successfully live an ascetic lifestyle are rewarded far beyond ordinary Christians; those who live an ascetic lifestyle but are too proud are forced to wait for their reward; and those who attempt but fail at an ascetic lifestyle are punished with eternal torture.[4]

Versions

Greek copies of the texts are rare; those that exist contain many omissions. Of the Eastern versions – Syriac, Coptic, Amharic, Georgian – the Syriac are considered to be the most reliable. There is an Ethiopic version of the apocalypse which features the Virgin Mary in the place of Paul the Apostle, as the receiver of the vision, known as the Apocalypse of the Virgin.

The lost Greek original was translated into Latin as the Visio Pauli, and was widely copied, with extensive variation coming into the tradition as the text was adapted to suit different historical and cultural contexts; by the eleventh century, there were perhaps three main independent editions of the text. From these diverse Latin texts, many subsequent vernacular versions were translated, into most European languages, prominently including German and Czech.[6]

The Visio Pauli also influenced a range of other texts again. It is particularly noted for its influence in the Dante's Inferno (ii. 28[7]), when Dante mentions the visit of the "Chosen Vessel"[8] to Hell.[6] The Visio is also considered to have influenced the description of Grendel's home in the Old English poem Beowulf (whether directly or indirectly, possibly via the Old English Blickling Homily XVI).[9]

Further reading

- Jan N. Bremmer and Istvan Czachesz (edd). The Visio Pauli and the Gnostic Apocalypse of Paul (Leuven, Peeters, 2007) (Studies on Early Christian Apocrypha, 9).

- Eileen Gardiner, Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante (New York: Italica Press, 1989), pp. 13–46, provides an English translation of the Latin text.

- Lenka Jiroušková, Die Visio Pauli: Wege und Wandlungen einer orientalischen Apokryphe im lateinischen Mittelalter unter Einschluß der alttschechischen und deutschsprachigen Textzeugen (Leiden, Brill, 2006) (Mittellateinische Studien und Texte, 34).

- Theodore Silverstein and Anthony Hilhorst (ed.), Apocalypse of Paul (Geneva, P. Cramer, 1997).

- J. van Ruiten, "The Four Rivers of Eden in the Apocalypse of Paul (Visio Pauli): The Intertextual Relationship of Genesis 2:10–14 and the Apocalypse of Paul 23:4," in García Martínez, Florentino, and Gerard P. Luttikhuizen (edd), Jerusalem, Alexandria, Rome: Studies in Ancient Cultural Interaction in Honour of A. Hilhorst (Leiden, Brill, 2003).

- Nikolaos H. Trunte, Reiseführer durch das Jenseits: die Apokalypse des Paulus in der Slavia Orthodoxa (München – Berlin – Washington, D. C.: Verlag Otto Sagner. 2013) (Slavistische Beiträge 490).

References

- Copeland, Kirsti (2006), The Wise, the Simple, the Pachomian Koinonia and the Apocalypse of Paul (PDF), retrieved 6 August 2020

- Ehrman 2005, p. xiv.

- Ehrman, D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

- Ehrman, Bart (2022). Journeys to Heaven and Hell: Tours of the Afterlife in the Early Christian Tradition. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 95–110. ISBN 978-0-300-25700-7.

- Ehrman, Bart (2003), Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew, Oxford Press, pp. xiv, ISBN 9780195141832

- Maier, Harry O. (2007). "Review of Die Visio Pauli: Wege und Wandlungen einer orientalischen Apokryphe im lateinischen Mittelalter, unter Einschluß der alttschechischen und deutschsprachigen Textzeugen". Speculum. 82 (4): 1000–1002. doi:10.1017/S0038713400011647. JSTOR 20466112.

- Several versions and commentaries on Inferno, Canto II, 28 of the Divine Comedy. Pietro Alighieri thinks it is an allusion to 2 Corinthians 12.

- Acts 9:15: But the Lord said unto him, Go thy way: for he is a chosen vessel unto me, to bear my name before the Gentiles, and kings, and the children of Israel:

- Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript, rev. edn (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003), pp. 38-41.

External links

- M.R. James' translation and commentary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924.

- Bibliography on the Apocalypse of Paul.