Old Polish

Old Polish language (Polish: język staropolski, staropolszczyzna) is the period in the history of the Polish language between the 10th and the 16th centuries, followed by the Middle Polish language.[1]

| Old Polish | |

|---|---|

| ięzyk Polſki | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈjɛ̃zɨk ˈpɔlʲskɨ] [ˈjɛ̃zɨk ˈpɔlʲskʲi] |

| Region | Central Europe |

| Era | developed into Middle Polish by the 16th century |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

0gi | |

| Glottolog | oldp1256 |

The sources for the study of the Old Polish language in the pre-written era are the data of the comparative-historical grammar of Slavic languages, the material of Polish dialects and several monuments of writing with Polish glosses; the sources of the written era are numerous monuments of the Latin language with Polish glosses and monuments created only in Polish: "Holy Cross Sermons" (Polish: Kazania świętokrzyskie), "Florian Psalter" (Polish: Psałterz floriański), "Mother of God" (Polish: Bogurodzica), "Sharoshpatak Bible" (Polish: Biblia szaroszpatacka) and many others.

The Old Polish language was spread mainly on the territory of modern Poland: in the early era of its existence – in the Polish tribal principalities, later – in the Polish kingdom.

History

The Polish language started to change after the baptism of Poland, which caused an influx of Latin words, such as kościół "church" (Latin castellum, "castle"), anioł "angel" (Latin angelus). Many of them were borrowed via Czech, which, too, influenced Polish in that era (hence e.g. wiesioły "happy, blithe" (cf. wiesiołek) morphed into modern Polish wesoły, with the original vowels and the consonants of Czech veselý). Also, in later centuries, with the onset of cities founded on German law (namely, the so-called Magdeburg law), Middle High German urban and legal words filtered into Old Polish. Around the 14th or 15th centuries the aorist and imperfect became obsolete. In the 15th century the dual fell into disuse except for a few fixed expressions (adages, sayings). In relation to most other European languages, though, the differences between Old and Modern Polish are comparatively slight; the Polish language is somewhat conservative relative to other Slavic languages. That said, the relatively slight differences between Old and Modern Polish are unremarkable considering that the chronological stages of other European languages that Old Polish is contemporary with are generally not very different from the Modern stages and many of them already labelled "Early Modern"; Old Polish includes texts that were written as late as the Renaissance.

Earliest written sentence

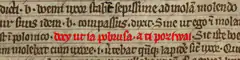

The Book of Henryków (Polish: Księga henrykowska, Latin: Liber fundationis claustri Sancte Marie Virginis in Heinrichau), contains the earliest known sentence written in the Polish language: Day, ut ia pobrusa, a ti poziwai (pronounced originally as: Daj, uć ja pobrusza, a ti pocziwaj, modern Polish: Daj, niech ja pomielę, a ty odpoczywaj or Pozwól, że ja będę mielił, a ty odpocznij, English: Let me grind, while you take a rest), written around 1270.

The medieval recorder of this phrase, the Cistercian monk Peter of the Henryków monastery, noted that "Hoc est in polonico" ("This is in Polish").[2][3][4]

Spelling

The difficulty the medieval scribes had to face was attempting to codify the language was the inadequacy of the Latin alphabet to some features of Old Polish phonology, such as vowel length and nasalization, or palatalization of consonants. Thus, Old Polish did not have a unified spelling. Polish glosses in Latin texts use latinized spelling, which often failed to distinguish between distinct phonemes.[5][6]

The spelling in the major works of Old Polish, such as the Holy Cross Sermons or the Sankt Florian Psalter is better developed. Their scribes tried to resolve the aforementioned issues in various ways, which led to each manuscript having separate spelling rules. Digraphs were commonly employed to write sounds not present in Latin, the letter ø or ɸ was introduced to spell the nasal vowels, and the basic Latin letters were now used consistently for the same sounds. Nevertheless, many features were still only rarely marked, for example vowel length.[5][6]

Parkoszowic

About 1440 Jakub Parkoszowic, a professor of Jagiellonian University was the first one to attempt a codification of Polish spelling. He wrote a tract on Polish orthographic rules (in Latin) and a short rhyme Obiecado (in Polish) as an example of their use. The following rules were proposed:[5][7]

- introduction of new letters of different shape to write hard (velarized) consonants, while soft (palatalized) consonant letters are left unchanged,

- doubling of vowel letters to mark long sounds, for example: aa – /aː/,

- use of the letter ø to write the short nasal vowel (øø for the long nasal vowel),

- use of the letter g to write /j/, reserving q for /ɡ/ instead,

- use of digraphs and trigraphs to distinguish between the various coronal fricatives and affricates,

among others.

Parkoszowic's proposal was not adopted. His conventions were judged to be impractical and cumbersome, and bore little resemblance to the spellings commonly used. However, his tract is of great importance to the history of the Polish language, as the first scientific work about the Polish language. It provides especially useful insight to contemporary phonology.[5][7]

Phonology

Over the centuries Old Polish pronunciation was subjected to numerous changes.

Consonants

Early Old Polish consonantal system consisted of the following phonemes. Since the precise realization of these sounds is unknown, the transcriptions used here are meant to be approximations.[7]

| Labial | Coronal | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hard | soft | hard | soft | soft | soft | hard | |

| Nasal | m | mʲ | n | ɲ | |||

| Stop | p b | pʲ bʲ | t d | tʲ dʲ | k ɡ | ||

| Affricate | t͡sʲ d͡zʲ | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | |||||

| Fricative | (f) v | (fʲ) vʲ | s z | sʲ zʲ | ʃ ʒ | x | |

| Approximant | ɫ | lʲ | j | ||||

| Trill | r | rʲ | |||||

Relatively few consonantal changes occurred during the Old Polish period. The most important concerned the realization of the soft coronal obstruents. Of these /tʲ/, /dʲ/, /sʲ/ and /zʲ/ strengthened their palatalization and became alveolo-palatal, and the former two were affricated. The resultant sounds were similar to their modern Polish counterparts: /t͡ɕ/, /d͡ʑ/, /ɕ/ and /ʑ/.[7] This change happened very early, starting already in the middle of the 13th century as evidenced by spelling.[5]

On the other hand, the palatalization of the affricates /t͡sʲ/ and /d͡zʲ/ weakened and by the middle of the 15th century they became hard.[5]

Somewhere around the 14th century the phoneme /rʲ/ came to be pronounced with considerable friction, probably resulting in a sound similar to Czech /r̝/ (but by then probably still palatalized: /r̝ʲ/).[5][7]

The very end of the Old Polish period (starting in the 15th century) sees the palatalization of the velar prosives /k/ and /ɡ/ before front oral vowels to [kʲ] and [ɡʲ] – the so-called "fourth Slavic palatalization". This distinction was later phonemicized with the introduction of borrowings which had hard velars before front vowels. Note that this change did not affect the velar fricative /x/ or velars before the front nasal vowel /æ̃~ɛ̃/.[5][7] Not all regional varieties handled this change in the way here described, most notably in Masovia.

After these alternations the late Old Polish consonant system presented itself thusly:[5][7]

| Labial | Coronal | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hard | soft | hard | soft | soft | soft | soft | hard | |

| Nasal | m | mʲ | n | ɲ | ||||

| Stop | p b | pʲ bʲ | t d | [kʲ] [ɡʲ] | k ɡ | |||

| Affricate | t͡s d͡z | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | t͡ɕ d͡ʑ | |||||

| Fricative | f v | fʲ vʲ | s z | ʃ ʒ | ɕ ʑ | x | ||

| Approximant | ɫ | lʲ | j | |||||

| Trill | r | r̝ʲ | ||||||

Vowels

Early Old Polish vocalic system consisted of the following phonemes. As mentioned, the sound qualities are approximations.[6][7]

| front | central | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| close | i iː | ɨ ɨː | u uː |

| mid | ɛ ɛː | ɔ ɔː | |

| open | æ̃ æ̃ː | a aː | ɑ̃ ɑ̃ː |

[ɨ] and [ɨː] were in complementary distribution with [i] and [iː] respectively, and the pairs can be regarded as allophones.[6]

All vowel phonemes occurred in pairs, one short and one long. Long vowels emerged in Old Polish from three sources:[5][6]

- compensatory lengthening after the deletion of weak yers before a voiced consonant (e.g. PS rogъ > OP rōg, PS gněvъ > gniēw, PS stalъ > OP stāł; see Havlík's law)

- from the contraction of various sequences of two vowels separated by /j/ (e.g. PS sějati > OP siāć, PS dobrajego > OP dobrēgo, PS rybojǫ > OP rybǭ)

- inherited from Proto-Slavic neoacute accent

During the Old Polish period vowel length ceased to be a feature distinguishing phonemes. The long high vowels /iː/, /ɨː/ and /uː/ merged with their short counterparts with no change in quality. The fate of the remaining long oral vowels was different: they also lost their length, but their articulation became more closed and so they remained dintinct from their old short counterparts. Thus /ɛː/ changed to /e/ and /ɔː/ changed to /o/. The earlier long /aː/ also gained roundedness and became /ɒ/. This process was complete in the late 15th century. The higher vowels are traditionally called pochylone ("skewed") in Polish.[5][6][7]

The nasal vowels developed differently. Old Polish continued to have four nasal vowels until the 14th century, when they merged in respect to quality, but retained the length distinction. The new system therefore had only two nasal vowels: short /ã/ (from earlier /æ̃/ and /ɑ̃/) and long /ãː/ (from earlier /æ̃ː/ and /ɑ̃ː/). In the 15th century when vowel length was disappearing the two nasals retained the old length distinction through changes in quality, like the other non-high vowels. The short nasal was fronted to /æ̃~ɛ̃/ and the long backed to /ɒ̃~ɔ̃/ and lost its length (both with differing dialectal realizations).[5][6][7]

The described changes led to the creation of the late Old Polish vocalic system:[6][7]

| front | central | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| close | i | ɨ | u |

| mid | ɛ e | ɔ o | |

| open | æ̃~ɛ̃ | a | ɒ ɒ̃~ɔ̃ |

Accent

Although stress was never marked in writing, its development in Old Polish can be partially inferred from certain other phonetic changes.

In the oldest works the verbal suffix -i/-y of the 2nd & 3rd ps. sg. imp. is dropped in some verbs, but retained in others. A comparison with East Slavic languages shows that the suffix remained when it was stressed in Proto-Slavic. Examples:

- Bogurodzica spuści – Russian спусти́ spustí

- Bogurodzica raczy – Russian рачи́ račí

- Bogurodzica usłysz – Russian услы́шь uslýšʹ

- Sankt Florian Psalter chwali – Russian хвали́ xvalí

- Holy Cross Sermons wstań – Russian вста́нь vstánʹ

Because of this it is thought that early Old Polish had free, lexical stress inherited from Proto-Slavic.[5][6]

Frequent ellipsis of the second vowel in trisyllabic words in the 14th and 15th century (wieliki > wielki, ażeby > ażby, iże mu > iż mu, Wojeciech > Wojciech) point to the conclusion that by that time fixed initial stress had developed.[5] The initial stress in the peripheral Podhale and southern Kashubian dialects (now considered a separate language but still part of the Lechitic dialect continuum) are taken to be remnants of earlier widespread initial stress.[6]

Morphology

In this section the Old Polish sounds are spelled the same as their primary reflexes using modern Polish orthography, except that non-high long vowels are marked with a macron: ā, ē, ō. The represented state of the nasal vowels is that of the 14th century – two nasal vowels differing in length. This is represented by letters from modern Polish orthography: ę for /ã/ and ą for /ãː/, for the sake of easier comparison with modern forms and proper display.

Nouns

Old Polish nouns declined for seven cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, instrumental, locative and vocative; three numbers: singular, dual, plural; and had one of three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine or neuter.[5][6]

The following is a simplified table of Old Polish noun declension:[6]

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hard a-stems | soft a-stems | i-stems | ||||

| Singular | Nom. | ∅ | -o -e -ē -ę | -a | -a -ā -i | ∅ |

| Gen. | -a -u | -a -ā | -y | -e -i (-ēj) | -i | |

| Dat. | -u -owi | -u (-owi) | -e | -i | ||

| Acc. | =Nom. or =Gen. | =Nom. | -ę | -ą | ∅ | |

| Ins. | -em -'em | -em -'em -im | -ą | |||

| Loc. | -'e -u (-i) | -e | -i | |||

| Voc. | -'e -u | =Nom. | -o | -e (-o) | -i | |

| Dual | Nom. Acc. |

-a | -'e -i | -i | ||

| Gen. Loc. |

-u | |||||

| Dat. Ins. |

-oma | -ama | -ma | |||

| Plural | Nom. | -i -owie -e | -a -ā | -y | -e | -i |

| Gen. | -ōw -i (∅) | ∅ -i | ∅ | -i | ||

| Dat. | -ōm -'ēm -ām | -ōm (-ām) | -ām | |||

| Acc. | -i -y -'e | =Nom. | =Nom. | |||

| Ins. | -mi -y | -ami (-mi) (-y) | -mi -ami | |||

| Loc. | -'ech (-ach) | -ach (-'ech) | -'ech (-ach) | |||

Forms in parentheses are encountered sporadically, or begin appearing at the very end of Old Polish period (during the transition to Middle Polish). An apostrophe before a suffix means that it triggered softening of the preceding consonant. i-stems are also called consonantal stems.

Although Old Polish inherited all of the inflectional categories of Proto-Slavic, the whole system was subject to a fundamental reorganization. The Proto-Slavic inflection paradigms were applied based on the shape of the stem, but this had been obscured by many phonetic changes. Consequently, the endings began being assigned based primarily on the lexical gender of nouns, which previously was not the primary consideration (although stem shape still played a role in certain cases). Many endings were lost from Proto-Slavic and others, often those which were more distinct, took their place.[5][6]

Although many of the above endings are the same as modern Polish, they did not necessarily have the same distribution. In classes which had a choice of two or more endings, these were commonly interchangeable, while in the modern language some words have stabilized and only accept one.[6][7]

The modern Polish distinction in animacy in masculine declension was only beginning to appear in Old Polish. The most visible symptom of this trend was the use of the genitive of masculine animate nouns in the singular in place of the accusative. This was directly caused by the fact that the accusative of all masculine nouns used to be identical with the nominative, causing confusion as to which of two animate nouns was the subject and which the direct object due to free word order: Ociec kocha syn – "The father loves the son" or "The son loves the father". The use of the genitive for the direct object solves this issue: Ociec kocha syna – unambiguously "The father loves the son". Such forms are ubiquitous already in the oldest monuments of the language, although exceptions still happen occasionally.[6][7]

Verbs

Old Polish verbs conjugated for three persons; three numbers: singular, dual, plural; two moods: declarative and imperative; and had one of two lexical aspects: perfective or imperfective. There was also the analytical conditional mood, formed by the aorist of the verb być "to be" and an old participle form.[5][6]

Significant changes from Proto-Slavic occurred in the usage of tenses. The ancient aorist and imperfect tenses were already in the process of dissapearing when the language was first attested. In the oldest texts of the 14th and 15th century these forms number only 26, and neither of the tenses show the whole inflection paradigm. The only exception was the aorist of być "to be", which survived and came to be used to form the conditional mood.[5][6][7]

The role of the past tense was taken up by a new analytical formation, composed of the present of być and the old L-participle of a verb.[5][6]

Literature

- The Gniezno Bull (Polish: Bulla gnieźnieńska) a papal bull containing 410 Polish names, published 7 July 1136 (This document can be viewed in Polish wikisource)

- Mother of God (Polish: Bogurodzica) 10th–13th centuries, the oldest known Polish national anthem

- The Book of Henryków (Polish: Księga henrykowska, Latin: Liber fundationis) – contains the earliest known sentence written in the Polish language.

- The Holy Cross Sermons (Polish: Kazania świętokrzyskie) 14th century

- St. Florian's Psalter (Polish: Psałterz floriański) 14th century – a psalmody; consists of parallel Latin, Polish and German texts

- Master Polikarp's Dialog with Death (Polish: Rozmowa Mistrza Polikarpa ze Śmiercią, Latin: De morte prologus, Dialogus inter Mortem et Magistrum Polikarpum) verse poetry, early 15th century

- Lament of the Holy Cross (Polish: Lament świętokrzyski, also known as: Żale Matki Boskiej pod krzyżem or Posłuchajcie Bracia Miła), late 15th century

- Bible of Queen Sophia (Polish: Biblia królowej Zofii), first Polish Bible translation, 15th century

Example

- Ach, Królu wieliki nasz

- Coż Ci dzieją Maszyjasz,

- Przydaj rozumu k'mej rzeczy,

- Me sierce bostwem obleczy,

- Raczy mię mych grzechów pozbawić

- Bych mógł o Twych świętych prawić.

(The introduction to The Legend of Saint Alexius – 15th century)

References

- Długosz-Kurczabowa, Krystyna; Dubisz, Stanisław (2006). Gramatyka historyczna języka polskiego (in Polish). Warszawa (Warsaw): Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. pp. 56, 57. ISBN 83-235-0118-1.

- Digital version Book of Henryków in latin

- Barbara i Adam Podgórscy: Słownik gwar śląskich. Katowice: Wydawnictwo KOS, 2008, ISBN 978-83-60528-54-9

- Bogdan Walczak: Zarys dziejów języka polskiego. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, 1999, ISBN 83-229-1867-4

- Kuraszkiewicz, Władysław (1972). Gramatyka historyczna języka polskiego (in Polish). Warszawa: Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych.

- Rospond, Stanisław (1973). Gramatyka historyczna języka polskiego (in Polish). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Klemensiewicz, Zenon (1985). Historia języka polskiego (in Polish). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.