Andrey Bogolyubsky

Andrew I (ca. 1111 – 28 June 1174), his Russian name in full, Andrey Yuryevich Bogolyubsky[1] (Russian: Андрей Ю́рьевич Боголюбский, lit. Andrey Yuryevich of Bogolyubovo), also referred to as Andrei I Yuryevich and Andrei the Pious, was Grand prince of Vladimir-Suzdal from 1157 until his death. Andrey accompanied Yuri I Vladimirovich (Yury Dolgoruky), his father, on a conquest of Kiev, then led the devastation of the same city in 1169,[1][2] and oversaw the elevation of Vladimir as the new capital of northeastern Rus'[1] (and so the decline of Kievan rule). Andrey has been referred to in the West as the "Scythian Caesar", He was canonized as a saint in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Andrey Bogolyubsky | |

|---|---|

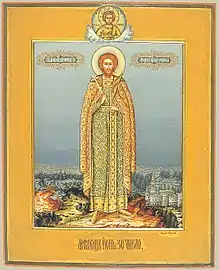

Russian icon of Saint Andrey Bogolyubsky | |

| Passion Bearer | |

| Born | c. 1111 |

| Died | 28 June 1174 (aged 62/63) |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Dormition cathedral, Vladimir |

| Feast | 30 June, 4 July (burial) |

| Attributes | Clothed as a Russian Grand Prince, holding a three-bar cross in his right hand |

Biography

Andrey Bogolyubsky was born ca. 1111, to a Greek mother[3] and to Yuri I Vladimirovich (Russian: Юрий Владимирович), commonly known as Yuri Dolgoruki (Russian: Юрий Долгорукий), a prince of the Rurik dynasty,[4][1] who proclaimed Andrey a prince in Vyshgorod (near Kiev).

Andrey left Vyshgorod in 1155 and moved to Vladimir. After his father's death (1157), he became Knyaz (prince) of Vladimir, Rostov and Suzdal.[1] He proceeded to attempt to unite Rus' lands under his authority, struggling persistently for submission of Novgorod to his authority, and conducting a complex military and diplomatic game in South Rus'. In 1162, Andrey sent an embassy to Constantinople, lobbying for a separate metropolitan see in Vladimir. In 1169 his troops sacked Kiev, devastating it as never before.[2][5] After plundering the city,[6] stealing much religious artwork, which included the Byzantine "Mother of God" icon.[7]: p.100 Andrey appointed his brother Gleb as prince of Kiev, in an attempt to unify his lands with Kiev.[8] Following his brother's death in 1171, Andrey became embroiled in a two-year war to maintain control over Kiev, which ended in his defeat.[8]

Andrey established for himself the right to receive tribute from the populations of the Northern Dvina lands. As "ruler of all Suzdal land", Bogolyubsky transferred the capital to Vladimir, strengthened it, and constructed the Assumption Cathedral,[9] the Church of the Intercession on the Nerl,[10] and other churches and monasteries. Under his leadership Vladimir was much enlarged, and fortifications were built around the city.[11]

During Andrey's reign, the Vladimir-Suzdal principality achieved significant power—he "made Vladimir the centre of the grand principality"[1]—and it became the strongest among the Kievan Rus principalities. The expansion of his princely authority, and his conflicts with the upper nobility, the boyars, gave rise to a conspiracy that resulted in Bogolyubsky's death on the night of 28-29 June 1174, when twenty of them burst into his chambers and slew him in his bed.[7]: p.100 [1] As the Encyclopædia Britannica notes, Andrey

placed a series of his relatives on the now secondary princely throne of Kiev... [and later] compelled Novgorod to accept a prince of his choice. In governing his realm, [he] not only demanded that the subordinate princes obey him but also tried to reduce the traditional political powers of the boyars... within his hereditary lands. In response, his embittered courtiers formed a conspiracy and killed him.[1]

Descendents

With his wife, Andrey Bogolyubsky had one son, Yuri, who became the husband of Queen Tamar of Georgia.

Legacy

The ancient icon, Theotokos of Bogolyubovo, was painted at the request of Andrey Bogolyubsky.[12] He later brought it with him to Vladimir, the city whose name the icon now bears.

Andrey had the castle, Bogolyubovo, built near Vladimir, and it would become his favorite residence[11] and the source of his nickname, "Bogolyubsky".

See also

References

- Andrew I at the Encyclopædia Britannica "Andrew made Vladimir the centre of the grand principality and placed a series of his relatives on the now secondary princely throne of Kiev. Later he also compelled Novgorod to accept a prince of his choice. In governing his realm, Andrew not only demanded that the subordinate princes obey him but also tried to reduce the traditional political powers of the boyars (i.e., the upper nobility) within his hereditary lands. In response, his embittered courtiers formed a conspiracy and killed him."

- Plokhy, Serhii (2006), The Origins of the Slavic Nations (PDF), Cambridge University Press, p. 42, ISBN 9780521864039, archived from the original (PDF) on March 29, 2017

- Vernadsky, George (1944). A History of Russia: New Revised Edition. p. 37.

The mother of Vladimir Monomakh was a Greek princess, and the mother of Andrei Bogolubsky was also a Greek.

- Presniakov, Alexander E. (1986) [1918]. The Tsardom of Muscovy. Translated by Price, Robert F. Academic International Press (orig., Petrograd). pp. ix–x. ISBN 9780875690902.

- Martin, Janet (2004) [1986]. Treasure of the Land of Darkness: The Fur Trade and Its Significance for Medieval Russia. Cambridge University Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780521548113.

- "Russian Rulers: Andrey Yurievich Bogolyubsky", Russia the Great, retrieved August 7, 2007

- Martin, Janet (1995). Medieval Russia: 980-1584. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521368322.

- Pelenski, Jaroslaw (1988). "The Contest for the "Kievan Succession" (1155-1175): The Religious-Ecclesiastical Dimension". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 12/13: 776. JSTOR 41036344.

- Brumfield, William Craft (2013). Landmarks of Russian Architecture. Routledge. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9781317973256.

- Shvidkovskiĭ, Dmitriĭ Olegovich (2007). Russian Architecture and the West. Yale University Press. p. 36. ISBN 9780300109122.

- Martin (1995), p. 84.

- ""Bogolyubov" Icon of the Mother of God". Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 22 June 2021.